Academic photo essay nominated for the 2024 Vassar Anthropology Department Lilo Stern Writing Prize.

I see my transition as a group activity. Far from individual, I have relied on building a trans community to make these changes in my life that bring me closer to self-actualization and fulfilling the possibilities of who I can be. As the passing of discriminatory anti-trans legislation threatens trans rights across the world, I observe fearmongerers who distort this relationship of community building, who push claims of trans indoctrination and misinformation. However, my experiences have proven that being in trans community is one of the most powerful things I have felt. Without other trans people, I would not have known the reality of transition and the possibilities that have been hidden from me. Through this photo essay, I aim to approach the crucial interdependence of transitioning from a subjective lens. My selection of photos documents my own specific experience of transitioning in the context of building trans community and depending on others. In a hyper-individualist yet conformist society, I find power in acknowledging the specificity of my interdependence.

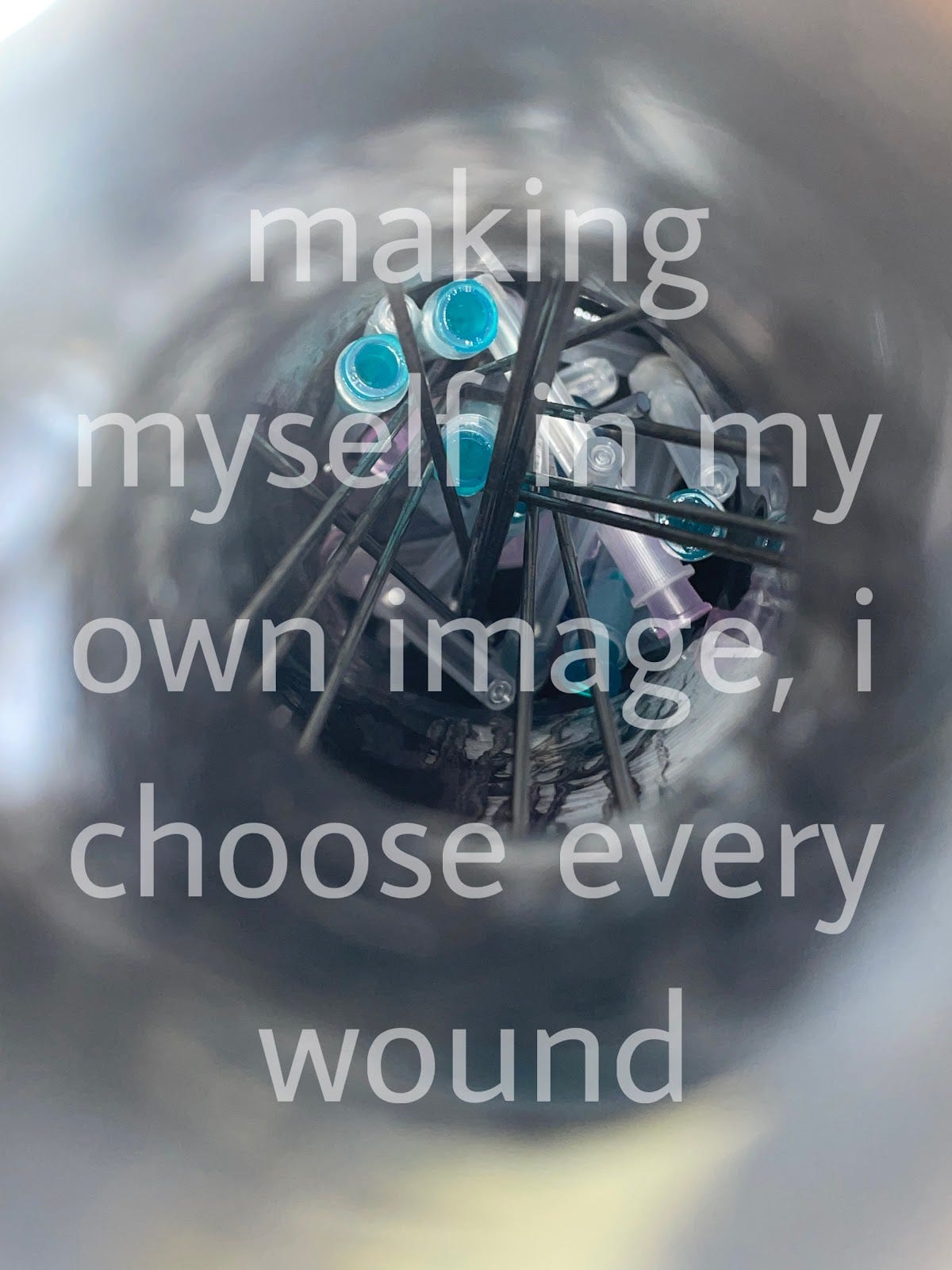

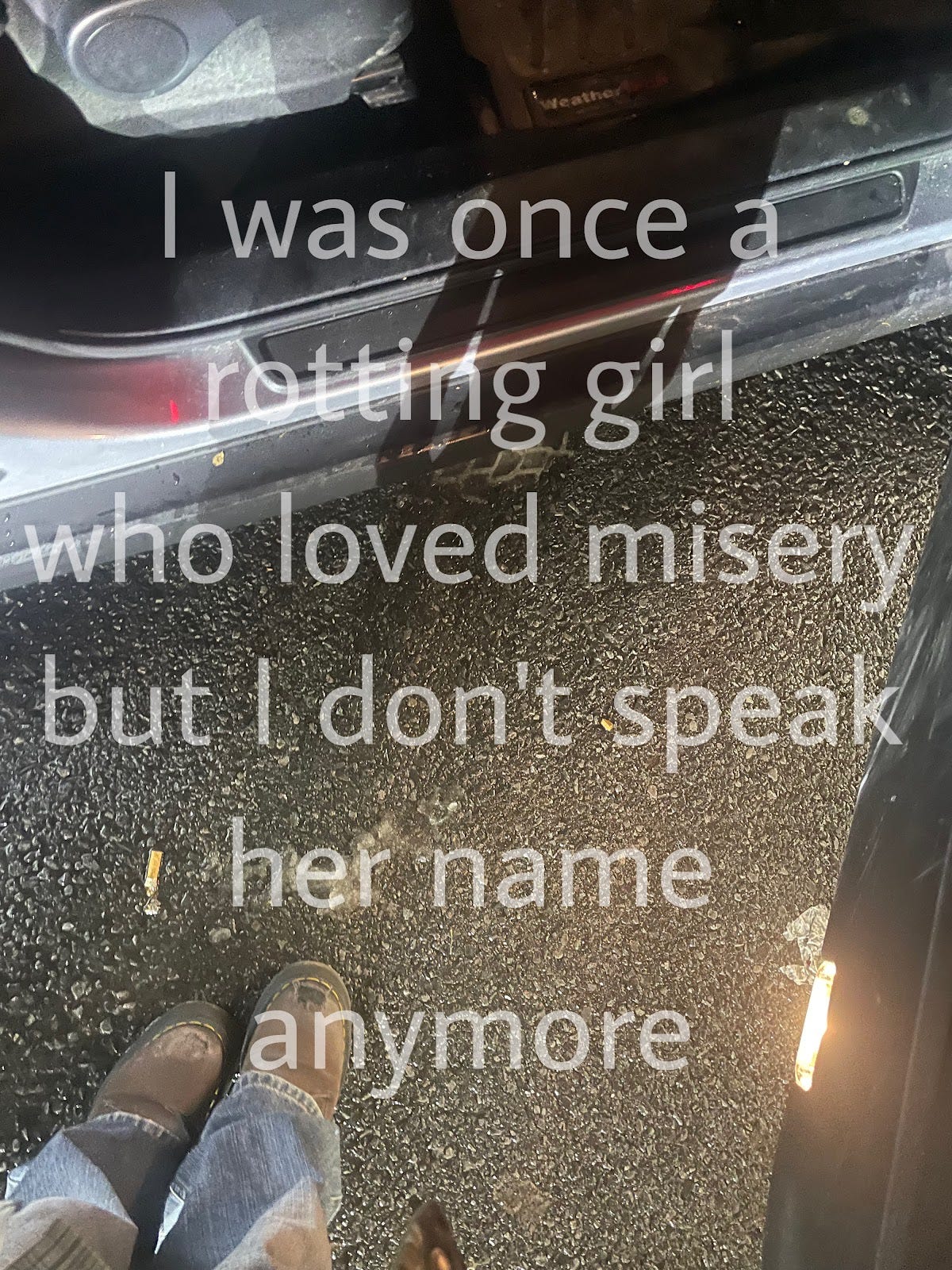

In my photo essay, the images I use fragment the community experience of transition into snapshots of individual moments. Crucially, the framing of my photographs immerses viewers in close-up moments experienced through the phone camera's lens. During our Visual Ethnography class session on February 12th, Malachi directed our attention to the use of aspect ratio in Laurian R. Bowles’ “Doing the Snap: Storytelling and Participatory Photography with Women Porters in Ghana”. As Malachi pointed out, the aspect ratio in Bowles’ article changed with each photo, reflecting the specific moment and context of each individual image. Accordingly, I chose to maintain the aspect ratio of my phone camera. In conjunction with the angles I chose for my photographs, this choice immerses the viewer in my point-of-view, experiencing each moment of community interdependence from my hyper-subjective lens. In “The Affective Lens”, Brent Luvaas experiments with street photography and immersion. Discussing ideas of being in the center of the action with street photography, Luvaas states that “like virtual reality films or POV pornography, [close-up photographs] place the viewer into the center of the action, erasing their own status as a medium (Bolter and Grusin 2000). The effect, for the viewer, is the illusion of immediacy” (169). Crucially, Luvaas describes the immediacy of the immersed close-up shot as an “illusion”. These POV shots have the potential to “erase” the medium of the camera, for better or for worse. In response to this critique, my use of captioning and maintenance of my phone’s aspect ratio brings attention back to the way I’ve used my phone camera to mediate these moments.

The way I’ve stylized my images also responds to hyper-specific conventions of representing transmasculine experiences online. In particular, I have chosen to reference and respond to a genre of images and written posts dubbed “forcemasc” first popularized on Tumblr. Parodying more widespread and controversial forced feminization or “sissification” online content, “forcemasc” playfully turns the goal of feminine beauty on its head. Instead, varying notions of transmasculinity become fetishized and desirable. Much of “forcemasc” imagery consists of poetic text often referencing the use of testosterone and other forms of physical transition imposed over photographs depicting masculinity, often with undertones of homoeroticism. In “Why do ‘Good’ Pictures Matter in Anthropology?”, Leon-Quijano emphasizes the importance of engaging with larger social contexts and histories of representation when photographing subjects. Leon-Quijano suggests that “a good picture might embrace the politics of visual representation from a critical standpoint that questions the social depiction of imaged subjects” (574). Through my visual response to the “forcemasc” genre, I question its particular social depiction of transmasculine subjects. Primarily, I push back against the hyper-visibility of white masculinity evidenced by the overwhelming use of images of conventionally attractive white men in “forcemasc” image edits. Additionally, I am curious about how most of the background images used are found images, rather than images produced by the individuals who make these edits. In contrast, I choose to leave faces out of the images I personally captured for my edits. Rather than universalizing a white transmasculine experience, my images pull at the hyper-subjectivity of my own lived experience in conversation with the conventions of “forcemasc” imagery.

Audience also comes into play as I experiment with subjectivity in my photo essay. While planning and constructing my photo essay, I considered that my audience was most likely not as deeply immersed in online transmasculine culture as I am. However, at the same time, I did not want to talk down to my audience or simplify the nuances of the experiences I hoped to document. One way I did this was to turn to “small anthropology,” as Sobers discusses in “The Future of Visual Anthropology in the Wake of Black Lives Matter”. Sobers states, “My approach to anthropology is ‘small anthropology’: the micro, the specific. Anthropology has been conducted on my people and it’s been misrepresentative, and I know there are huge flaws in grand narratives and universals. I tend toward a much humbler approach, where I don’t attempt to make universal claims” (409). Following this logic, I chose to zoom in, both literally and figuratively, on the details of trans interdependence. By looking at the nitty-gritty and the everyday, my photo essay refuses to generalize a universal depiction of trans interdependence. Furthermore, my use of first-person, casual captions limits my audience’s reception of my photo essay to the specific experiences I capture. As MacDougall describes in “The Visual in Anthropology,” “to anthropology the visual often seems uncommunicative and yet somehow insatiable. Like the tar baby, it never says anything, but there is always something more to be said about it. Words, on the other hand, speak out and thus define their own terrain” (217). By playing with narrative specificity in my captions, I use words to define the terrain of how my depictions of trans interdependence can be received by the audience. I do not claim to represent every trans experience, and center this claim in the way I present my photo essay.

Ultimately, I responded to the challenges surrounding my photo essay by centering a hyper-subjective, “small anthropology” approach to visual ethnography. My photo essay speaks to a community experience but refuses to conflate community with the universal. I draw from my unique personal experiences and enter into conversations with the niche cultural contexts I am a part of. One of the most crucial takeaways I’d like for cisgender audiences to understand from my photo essay is that transition looks so different for everyone, but it happens in community. I hope that I can achieve some part of this by approaching this group experience of interdependence from a first-person, hyper-specific visual perspective.

Bowles, Laurian R. “Doing the Snap: Storytelling and Participatory Photography with Women Porters in Ghana.” Visual Anthropology Review, vol. 33, no. 2, Nov. 2017, pp. 107–118, https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12129.

Leon-Quijano, Camilo. “Why do ‘Good’ Pictures Matter in Anthropology?” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 37, no. 3, 18 Aug. 2022, pp. 572–598, https://doi.org/10.14506/ca37.3.11.

Luvaas, Brent. “The Affective Lens.” Anthropology and Humanism, vol. 42, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 163–179, https://doi.org/10.1111/anhu.12190.

MacDougall, David. “The Visual in Anthropology.” The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2006, pp. 213–226.

Mullings, Sireita, et al. “The Future of Visual Anthropology in the Wake of Black Lives Matter.” Visual Anthropology Review, vol. 37, no. 2, Sept. 2021, pp. 401–421, https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12253.